THE BORNEO CASE

By Giuseppe de Salvatore, Filmexplorer.ch

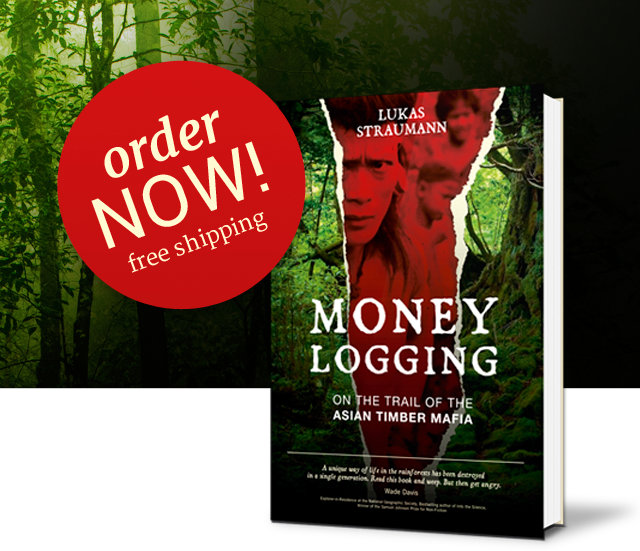

After Daniel Schweizer’s Trading Paradise (see our review), Völker Koepp’s Landstück (see our review) and Mehdi Sahebi’s MIRR, here yet another documentary film on the question of land exploitation comes to Swiss cinemas. The duo Erik Pauser and Dylan Williams tell the complex story of a very simple but extreme case of the exploitation of land. Without respecting the nomadic inhabitants of Malaysian Borneo, or Sarawak, Abdul Taib Mahmud – formerly the Chief Minister of the region for 33 years – became a billionaire taking advantage of the logging industry and palm oil plantations, which resulted in the dramatic deforestation and the construction of large dams that have destroyed the land and its ecosystem. Already in the Nineties, the Swiss human rights activist, Bruno Manser, together with Mutang Urud, launched massive international campaigns against the destruction of the rainforest and the evacuation of people, among which the Penan were particularly affected. Bruno Manser disappeared (or was made to disappear?) in the forest in 2000 and Mutang Urud was exiled to Canada. The Borneo Case is the story of an inquiry, initiated by an independent Malaysian radio station in London and reinforced by Lukas Straumann and the Bruno Manser Foundation in Basel, who were able to motivate Urud to return to activism.

The film takes the form of an investigative report and has nothing special to say as film, but its content, the incredible story it tells, is a really burning topic. We discover a widespread system of corruption and money-laundering involving big banks, from Deutsche Bank to various Swiss banking institutions. What makes this story a “case”, and a very special one, is the fact that, for once, it finishes with a happy ending. After several years of information campaign against him, in 2014, Taib stepped down and the new government was formed that would stop the palm oil economic program and the work at the largest dam, the Bakun Dam, saving the territories in which the Penan live; other dams are still under construction and the logging industry will continue to operate, but at least some form of respect and compromise has begun to catch on.

How was it possible? How could a little group of activists actually create problems for a large system of interests backed by the enormous financial powers of major banks? From the dramaturgy of the film, it seems clear that the turning point was during the five-minute-long presentation that Straumann and Urud were allowed to give at the annual meeting of Deutsche Bank’s actionists. They could pursue a legal course, which strengthened their information campaign and made it more incisive and dangerous. The lesson to learn is not only that one should always fight against any abuse of power, but more precisely that we shouldn’t forget that financial power is built on the credibility that we give it – at least in the countries where the justice system works and violence does not block the democratic rights of the citizens.

From this point of view, the projection of a film like The Borneo Case, our watching it, and the circulation of its message become part of our eventual contribution to an active resistance against any abuse of power. It is precisely this performative aspect of the film that I want to emphasize as being its main value and force, which amounts also to not forgetting the effective power that all of us have, here in the Western world, and to recalling that this power must be used and it must be defended – which is one of the essential aspects of Bruno Manser’s legacy. That is why The Borneo Case is also a European case and, more precisely, a Swiss case.

Hier finden Sie den ganzen Artikel

zurück